The AVICOM Sessions during the 26th ICOM General Conference in Prague 2022: Reports and Papers

AVICOM Contributions to the ICOM General Conference in Prague

Joint Session AVICOM & CECA – Digital media for the preparation, implementation and follow-up of the museum visit. Sense, superfluity or nonsense? (22 August 2022, 16:00 – 17.30, HYBRID FORMAT)

Dr. Michael H. Faber, Cultural Anthropologist, President of AVICOM, State Museum Director LVR Open-Air Museum Kommern (retired), Bonn, Germany: Communication and mediation: digital, analogue, personal? About Must-Have, Nice to Have and Nonsense

Michael Eulenstein, Artist, M.A. Cultural Education/Mediation, Hildesheim, Germany: Best practice examples based on website analysis. Results of the survey by the MPR-AVICOM-Project “The COVID 19 Challenge”

Wuyan Li, Postdoctoral Researcher, Shanghai Science and Technology Museum, Shanghai, China: Discussion Children’s Learning Effectiveness by Digital Media during Museum Visiting: Based on an Empirical Survey of Museum Visitors

Joint Session AVICOM & MPR & ICOM – The Covid 19 Challenge: Museums and their digital engagement in times of crises. Results of the Solidarity Project of AVICOM, MPR and ICOM Germany and other contributions (23 August 2022, 14:30 – 16:00, HYBRID FORMAT)

Introduction into the project by Dr. Klaus Staubermann, CEO ICOM Germany, Dr. Matthias Henkel, President of AVICOM, Director of the Museum Neukölln, Berlin, Germany and Dr. Michael H. Faber, Cultural Anthropologist, President of AVICOM, State Museum Director LVR Open-Air Museum Kommern (retired), Bonn, Germany

Michael Eulenstein, Artist, M.A. Cultural Education/Mediation, Hildesheim, Germany: Results of the survey by the MPR-AVICOM-Project “The COVID 19 Challenge”

Elisa Monsellato, Project Manager,Swapmuseum, Lecce, Italy & Carola Gatto, PhD Student University of Salento, Lecce, Italy: The impact of lockdown on public engagement and involvement in small and peripheral museums: the case study of Swapmuseum digital strategy

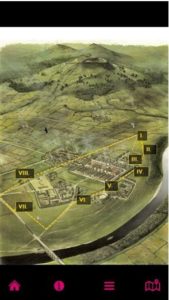

Prof. Alan Miller, Lecturer,University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom & Dr. Kamila Oles, Catherine Anne Cassidy, Research Fellow, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, United Kingdom: Enriching engagement through digital responses to COVID 19 VIC

Daniela Fuentes Arenas, Master in Cultural Heritage Management and Museology, Independent Museum Researcher, Santiago, Chile: The Role of virtual platforms of museums and cultural centers of Santiago de Chile throughout the social and health crises

Hosan Kim, Curator, The Kochon Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea & Jookyung Rhee, Director, Kochon Memorial Hall, Seoul, Korea: 2023 Pandemic Hero: Context based learning game as educational program in museum environment

Session AVICOM – News from the world of audiovisual and digital museum media (23 August 2022, 16:30 – 18:00, HYBRID FORMAT)

Elina Vikmane, research assistant, Latvian Museum Association; Research Centre at Latvian Academy of Culture, Rīga, Latvia: Characteristics of digitally innovative museums

Yuqiao Hu, PhD student, University of Leicester, School of Museum Studies, Leicester, United Kingdom: Rural youth engagement on Kuaishou: opportunities and challenges of Chinese museums on new social media platforms

Dr. Anna Maria Marras, research fellow, University of Turin, Turin, Italy: Conversational assistants, chatbot: how language technologies interact in the everyday life of museums

Mgr. Aleš Kapsa, Program and cultural educator, Video specialist, Muzeum Jana Amose Komenského, Uherský Brod, Czech Republic: The Labyrinth and the Theatre on the Stage of the World

Indrani Bhattacharya, Professor of Museology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India & Mr Supreo Chanda, Head of Museology, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India: Digital Assistance in Indian Museums’ Educational Programme Design

Kumiko Matsui, Postdoctoral Fellow, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., United States & Yuri Kimura, Curator, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba, Japan: Museums at risk by leaving 3D image policies unwritten

AVICOM Off-Site Meeting in the National Technical Museum with AVICOM’s Media Festival F@IMP 2021/2022 (25 August 2022, NON-HYBRID)

Session:

Jeanne Pommeau, curator and restorer, Národní filmový archiv, Prague, Czech Republic: The Digital paradox: Digital tools as a mean for valorization of materiality – the example of Lumière’s vintage prints

Mohamed Harb, lecturer, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt: Virtual Museum of Tutankhamun

Fatemeh – Kimia Amini Khashouei, Admin of social media ICOM Iran, Iranian National Museum of Science and Technology (INMOST), Tehran, Iran & Parastou Manteghi, Translater and Reasercher New Media, Privet Museum, Tehran, Iran: Report of 11,000 kilometers, digital historical narrative. See museums at home

Simona Chalupová, Director, Chrudim Puppetry Museum, Chrudim, Czech Republic: International cooperation during the pandemic: the Exhibition “Secrets of Wooden Puppets” in the Seoul Museum of History

After the session: F@imp Festival Ceremony and reception of the festival participants

Before, During and After the Visit

Critical questions to guide the choice of content for digital offers

Marie-Clarté O’Neill, Ecole du Louvre, Paris, President of CECA

A long time practice of applied research around exhibitions and the various media used to build a scenario easily shared with the visitors, has convinced me that , still too often, the digital offer has not yet reached a mature development. The question is certainly not anymore a reluctance of museums for the use of numeric communication tools. Cost or related expertise are usually the obstacles. But what is obvious is a relative awkardness in adapting these new possibilities to the already complex museum experience. Still rather seldom are the visiting experiences where a digital proposal brings visitors exactly what they need to enrich their experience. The contribution can be twofold : an appropriate technique supporting a relevant content. The choice for approaching this topic is here, clearly, the content, or more precisely considering digital offers from the perspective of their educational potential because this is the DNA of CECA . Another orientation is also chosen, taking into account only visits of museums presenting material heritage and the use of technologies in these environments.

If we decide to focus on educational potential, the question then arises of how can one decide that a content, whatever its support, is educational. Museology, the science around museums, offers two diverse means for reflecting around education effectiveness :

- Theories developed by recognised museum education theorists

Or

- Data issued from applied research on reception of museums by visitors

Before exploring this evironment, it may be useful to recall the definition adopted by CECA of education: education different from learning, education whose definition is based on the Latin ethymological roots of the word : e-ducere, leading further, making grow, helping to branch out, in museum environment, allowing visitors to have a rich personal experience.

Leaning on these two guidelines could help escaping the lure of novelty and the false certainty of unverified personal or shared opinions

Why, now, organize the reflection around specific moments of the museum experience :

before / during / after the visit? The question can be seen as : What happens during these three moments and how can a digital museum offering accompany visitors in each special experience,aiming to transform it into a fundamentally educational one?

“Temporality of reception” process, or the way visitors live in an exhibition is a process we have observed, with my Ecole du Louvre student team, over the course of our extensive research into four major Parisian exhibitions between 2000 and 2004 at the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais (Visions du futur, une histoiredes peurs et des espoirs de l’humanité, L’or des rois scythes, Matisse-Picasso, Vuillard) . We could witness there how visitors react very differently to these three moments of their experience and show needs linked very precisely to this specific chronolog. Starting from this field research, the concept of temporality of reception was further widely exploited by the french sociologist Antigone Mouchtouris, member of the research team, in numerous publications. Some of the patterns observed around the various moments of the visit have been confirmed by subsequent research

Given the enormity of the territory covered only a few examples will be analysed in order to try and design a methodological approach that will:

- Be likely to support the reflection of professionals, who are currently being asked to use digital technology without having any guidelines other than experiential ones

- Generate further research

Before the visit

The selected dimension chosen here is the expectation horizons i.e. what visitors bring with them before they come and what they can build around the experience they imagine before coming .

What can be evoked here are two scientifically validated theoretical assertion from education Sciences, namely :

- A satisfying and lasting intellectual experience is one that is connected to a previous personal experience

- New knowledge builds on prior knowledge

These trends could be verified through applied research among a large number of visitors to the four major Parisian exhibitions . Among those, one can quote a counter example , one of the results of the “before the visit” research

In the exhibition Visions of the Future: A History of Humanity’s Fears and Hopes, the title evoked, for the visitors interviewed, the future world, something linked to science fiction. The chosen communication images appeared to be very mysterious, not allowing a change of this first misconception.

Moreover, the first encountered object was problematic for the visitors and unable to adjust their expectation horizon as the beginning of the exhibition featured a mummy.

The consequences observed in the further course of the visits were a typical case of cognitive dissonance

- Difficulty in starting the meaning-making process when the theme was intellectually demanding, i.e. “how various ancient civilizations have imagined the future”

- Distraction at the beginning of the exhibition

Through this example, one sees that one of the roles of pre-visit offers, whatever the conveyed media, including the numeric ones, is therefore to encourage cognitive consonance to help the visitor enter the exhibition with the themes already in focus, to help foster rapidly harmonious psychological and intellectual activity and reach cognitive conguence.

Which practical consequences for the pre-visit ?

One of the aims of a pre-visit offer will therefore be, through a website or social networks, to first create the expectation horizons

- Describing the nature of the on-site offer (collections, programming, target audiences)

- Providing practical information

- Offering specific products (interviews, short videos, presentations of works, etc)Once covered this first step, one can also try to enrich the expectation horizons

A good example of this second trend can be found at Cernuschi Museum, Museum of Far Eastern Art of the City of Paris:

The founder of the museum gathered the bulk of the collection through a long journey through asian countries. Describing and showing through a map Henri Cernuschi’s journey, the beginning of an interest and of a collection, is a powerfull way to create a valid expectation horizon before the visit, either on line or on site. The visitor knows what type of objects will be on display and why these objects are on view in the galleries.

During the visit

Let us consider now one of the educational potentialities of any kind of numeric appliances during a museum visit.

The selected dimension is the importance of supporting observation of the objects and the meaning that visitors can draw from them

The justification provided comes again from applied research in museums. According to Daniel Schmitt’s field research (Museums of Strasbourg), the museum is largely seen by visitors as a place of proof: Though the evidence and the materiality of what is shown and through the evidence of the veracity of the information displayed.

What are the practical consequences of such a representation ?

The digital offer within the galleries must therefore accompany this conception by either supporting observation of these factual proofs, the displayed objects and, at the same time, by supporting solid meaning making around these same exhibits

We can select another dimension, like the importance that could be given to a strict insertion of the digital offers in the galleries inside the general process of meaning making expected from the visitors in a thematic display, for example.

The justification that can be here provided comes from the theories of constructivist museum education, a scientifically validated theory , advocated by world recognized museum education specialist like George Hein or Eileen Hooper-Greenhill, among others. The constructivist therory establishes that it is the visitor who constructs his visit by using, at the same time his intellectual and psychological tools and what the museum offers to make sense of what is on display.

The practical consequences of this process are the vital importance of a strict insertion of digital offers in the general process of a meaning making construction, requiring , at the same time, a strict relationship to the exhibits, the same relationship to the messages communicated and support for the psychological activity of visitors

Another dimension can be selected, of great importance in the present museologists’interest, the central role of interactivity

Justification can be found in the scientifically validated theory of John Dewey and his followers advocating the efficiancy of fostering intellectual and emotional activity through interactivity.

But interactivity , they say, should be together physical, sensory and intellectual , promote fun and memorization and foster interpersonal relationships.

Practical consequences of this theory should then promote looking for multiple modes of interactivity beyond the push button and trying to enrich the bond within the social group

After the visit

A recent research led by one of my student shows that very few attempts are made to provide a follow up of a visit, outside some pedagogical extensions for schools. What applied research has provided, again in the research around our four exhibitions in Paris is noting an evident mental overload immediately after the visit, relagating an after visit offer to a further moment and a outside place

Conclusion

Digital technology can no longer be seen as an attractive gadget because of its novelty because it is not . It should be always used to reinforce the universal educational power that museums can possess , up to the point of being able to replace absence with digital presence , the way archeologists use it, but having always in mind hints given by museum education trough recognized theories or applied research.

Communication and mediation: digital, analogue, personal? About Must-Have, Nice to Have and Nonsense

Dr. Michael H. Faber, State Museum Director (retired), President of AVICOM

Almost to the day, it is the third anniversary of an experience that continues to haunt me to this day. To this day, as an experienced museum director and previously long-time head of museum education at this museum, I like feel something post-traumatic stress disorder. What happened?

We AVICOM colleagues were invited to a museum in Osaka on the occasion of the last ICOM General Conference, which proudly offered us a virtual flight over the ancient imperial tombs. Each of us helped the other to put on the approximately 10 centimetre thick pilot’s glasses correctly, which were to give us the VR experience. And than I experienced the flight like a rollercoaster ride. I got afraid of heights, I felt dizzy, I tore the glasses off my head. And I was ashamed of some of the others who survived this virtual flight.

Since then, I know that virtual reality goggles are not for the faint-hearted. Maybe they are not for older people in general. Later, by the way, I discovered traditional exhibition boards in this museum with large aerial photos of these graves. Thank God! Here even scaredy-cats could enjoy looking at the graves from above – without barriers.

I will come back later to the keyword accessibility in connection with digital media. Before that, however, the question arises as to the relevance of the digital for the mediation of the analogue, i.e. the objects and their narrative context in the exhibition.

The digital exploration tour through a museum or an exhibition via website or app is a welcome offer for those who, for whatever reason, are not able to visit physically. Especially in the long period of the pandemic, museums have enormously expanded their offers in this regard and have thus also been able to retain their clientele. The digital visit is thus fundamentally a means of barrier reduction, has proven itself as a sustainable means of communication with the public and is thus at least a “nice to have”.

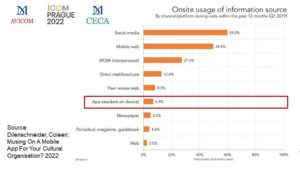

In onsite exhibition visits, however, the efficiency of the use of digital tours and object explorations is considered controversial, as studies have shown. The use of a device that can be borrowed, such as a tablet, is perceived by many as a hindrance, and accordingly they are little used – classic audio guides are the exception. We have the same situation concerning the mobile museum’s apps, resident on the visitor‘s device: The American „National Awareness, Attitudes and Usage Study“ (2017 /2019) has revealed that only 6.9 per cent of visitors use such an app onsite (2019). This study has also shown, that the increase of visitor’s satifaction by onsite usage of an app is only 0.7 per cent in relation to visitors not using that source. „This is alarming! Because increasing visitor satisfaction is the very point of (…) mobile applications!“ (Dilenschneider) For the communication of the original and its context, visitors still expect classic analogue displays. For a more detailed exploration of the object, for a deeper immersion in its context, interactive information systems installed directly near the object are perfectly adequate. Ultimately, they can provide all the information that would otherwise have to be retrieved via a mobile augmented reality app.

Comparing such stationary information systems with the mobile app, one can say: the former is a must-have, the latter is at best a nice additional toy that might fascinate younger visitors.

Do we need virtual reality or augmented reality applications? Do they satisfy visitors bringing the real exhibits closer? Virtual reality is in contrast to augmented reality: both offer in-depth information, but VR is based on reconstructions of what no longer exists. Virtual reality makes castles out of ruins, equips dinosaur skeletons with fur, eyes and teeth, sets the table in the baroque dining room with candlesticks, crockery, cutlery and all kinds of delicacies. As with all reconstructions, scientific accuracy determines the degrees of fact and fiction. And it is precisely here that the devil is in the detail: I know of countless VR apps whose content has not been sufficiently scientifically curated, but has been left too much to the production company. Nevertheless, a scientifically well-designed VR app can be good edutainment and bring objects closer – as long as you don’t wear 3-D glasses. Then you don’t see the real object at all!

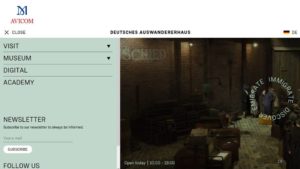

By the way, there has been an interesting empirical study with the title: „Does it move you? Evaluating the impact of virtual reality on the visitor experience at the German Emigration Center“ (Deutsches Auswandererhaus) in Bremerhaven. The evaluation focussed on the following four questions:

1) What impact(s) does virtual reality have on visitors’ emotions during an exhibit visit?

2) How does virtual reality affect visitor satisfaction?

3) What is the impact of virtual reality on learning in a museum setting? It is easy to imagine the potential entertainment value of VR in a museum, but will that entertainment translate into learning?

4) How do visitors experience real and virtual objects differently?

In the German Emigration Center, two rooms with the same theme were set up next to each other. In the room on the right, a complete living room was staged with conventional information displays. The left room, on the other hand, was empty. Here, there were only chairs on which the visitor could turn around and explore the room using a virtual reality app.

The effect of both exploration options, according to the results of the study with more than 700 test persons, was different, related to the two well known different types of emotions:

The first are “visitor-experience emotions.” You know that those emotions that relate to the experience of visiting the museum rather than the specific exhibit content. Such emotions are, for example: entertainment, joy, curiosity, excitement, trial and error. Visitor-experience emotions are significant because positive visitor experiences open the door to higher levels of learning and engagement.

The other type of emotions are “exhibit-subject emotions.” These emotions come directly from the exhibit narrative, and are pulled from the exhibit subjects’ experiences.

The results of the study showed the following:

Firstly, the physically staged right room aroused more exhibit-subject emotions, i.e. caused a more intensive engagement with what was shown, including the information provided. In the left-hand room, on the other hand, mainly visitor-experience emotions were aroused, i.e. related to interest in exploration, satisfaction, etc.

Secondly: The later questioning of the test persons regarding their memories of the details of what was shown confirmed that these were more pronounced in relation to the physical presentation. With reference to a high level of response in both types of emotions the offer of Virtual Reality may be a useful addition to classic forms of information. Therefore don’t you need 3D glasses. Corresponding VR technology is also offered for the tablet.

I encourage you to take a look at the study, which is exciting in terms of its method and results. You can find it in English on the website of the German Emigration Center:

https://www.dah-bremerhaven.de/museum4punkt0

Keyword website: With that I change the subject and come to what is really a must-have when preparing for a visit to the museum. Of course, almost all museums today have a website. But is this site constantly maintained, is it always up-to-date, does it provide precise information about the core competence, the corporate philosophy of the respective museum? And above all: Does it comply with the international norms of accessibility? Hand on heart: Do we museum scientists and museum educators really know exactly what counts in terms of accessibility and how to implement it. How to implement them in digital? At least those who produce digital media for us should be familiar with the standards, especially since these are now mandatory, at least for public institutions and their digital offers. By the way, the website of the German Emigration Center is a best practice example of barrier-free communication.

The EU Web Accessibility Directive (EU 2016/2102) from 2016, transposed into national law in 2018, has set deadlines by which websites, apps and other mobile applications must be barrier-free. This deadlines have already passed: for websites at September 2018 and for mobile apps at June 2021!

Internet sites must state in their accessibility declarations to what extent the sites meet the legal requirements and which elements are not yet accessible and for what reason. This also includes a feedback mechanism with which users can report barriers directly. State monitoring bodies monitor the barrier reduction processes. Governments are obliged to report to the EU.

If you are responsible for the digital presence of your museum, you, dear colleagues, are well advised to check these presences for accessibility. A whole range of tools are available for this purpose, that you can use by yourself, even it seems for someone a little bit complicated. Google’s „Lighthouse“, an open-source and automated tool for improving the performance, quality, and correctness of your web apps is just one example: When auditing a page, Lighthouse runs a barrage of tests against the page, and then generates a report on how well the page did. From here you can use the failing tests as indicators on what you can do to improve your app. Of course, you can also have your digital offerings checked for compliance with EU directives by companies specialized in this.

The standards prescribed in the EU Web Accessibility Directive are based on the rules set out by the World Wide Web Consortium in the “Web Content Accessibility Guidelines” (WCAG). The WCAG 2.1 describes four principles, 13 guidelines and 61 success criteria/conditions as well as recommended techniques for implementation.

Here I would like to mention only the four basic principles:

1) Perceptibility: Can everyone perceive it? This concerns the senses of sight, hearing and touch. This concerns, for example, contrast between text and background, easily readable font, screen readers for the blind, exclusive operation via the keyboard …, for the hearing impaired transcription of audio information, subtitling of videos and information in sign language.

2) Usability: This concerns motor impairments, mobility and strength. For example, coins need to be large enough to click on.

3) Comprehensibility: This concerns content and language, but also the complexity of the tool and its structure. Text information must be understandable, also available in plain language. The structure of the digital information must be predictable. Accessibility helps people with a wide range of impairments that we often don’t even think about: people with autism or ADHD can also be affected by bright colours, poor contrasts and inconsistent design.

4) Robustness: Here the technical dimension is addressed. Does the medium function without errors and is it compatible with other operating systems and end devices (responsive web design)?

Finally, I would like to come back to mobile apps and talk about Multi-Media Guides for pre-visit usage and the visit. First things first: Museums should consider apps because people are using apps more and more. Even the aforementioned survey on app usage by Colleen Dilenschneider reveals low usage rate for museum apps in comparison to other media for planning the museum visit. What are the reasons? A lot of museum apps are brutal: their design is poor, they lack key information like address and accessibility, they miss integration into the museum’s philosophy and strategy and the handling is simply horrible.

We know a lot of digital museum guides that are nothing more than route planners through the exhibition, with brief information and pictures of the exhibits. I have never understood why museums have had such crap produced for expensive money, but I do understand the producers who like to make money with it. The classic orientation flyer with exhibition map, the hall leaflet are cheaper and ready to hand for everyone on site – as long as you have thought about reprinting them in time.

If the guides are multimedia-based and meet the WCAG criteria for accessibility, they can be used equally by people with and without disabilities and will be better accepted by visitors in general. They are therefore a highly democratic means of communication.

Good multimedia guides can be handled in such a way that text, images, audio and video can be optimised for the different target groups on the one hand and also combined on the other. It is important to note that a good guide is not a special solution for people with disabilities, but it takes into account the special requirements of the user groups and guarantees technical accessibility. Its content design, structure, operating and selection tools follow the principle of being used by all people of all ages with different abilities on an equal footing and without assistance.

A best practice example is the Multimedia Guide of the Dresden State Art Collections, whose software was developed by the Technical University of Dresden for both smartphones and tablets. I would like to briefly mention a few characteristics: There are no nested menus, control elements have been replaced by easily understandable terms. When describing the paintings, the texts are provided in detail, but also in simple language, and a screen reader is available for the blind.

In addition, the exhibits are described audibly. Attention is also paid to the description of pictorial details that are imperceptible to the target group. For people with hearing impairments, the description of the paintings is in sign language, while the work is presented visually and with a text that can be read along.

A problem that I only discovered after completing my contribution: On the internet you only discover a conventional multimedia guide, but not the barrier-free version. When I called the museum, they only could give me the link to the conventional guide. Super bad service! If you offer digital services, please promote them, let them find!

Thank God, that the Dresden State Art Collections do not rely on digital tools for accessibility. They rely equally on personal mediation to people with disabilities. Barrier-free tours for the deaf, blind and visually impaired as well as tours in simple language are offered regularly. By my opinion, personal mediation to those target groups still remains a must-have.

Conclusion:

– As the example of Dresden shows, classic, personal and digital mediation must have the same importance in order to achieve inclusion for all. The digital complements the analog.

– Digital communication must follow international guidelines on accessibility. This starts with the website, continues via mobile apps and ends – we couldn’t talk about that – with the appropriate design of communication in social media.

– The use of digital media must be closely linked to the strategy of content and communication/museum education. Strategic processes require the implementation of digital communication planning right from the start. Please consider very critically, dear colleagues, what is necessary and makes sense, what could be more of a bit of luxury and what remains nonsense.

– Keep an eye on the cost-benefit ratio: Wouldn’t it make sense to put the money that a complex and then for some reason even short-lived app costs into personal placement, into living guides welcoming the visitors, exploring the objects together with them? Have conventional mediation and communication have not had their day. And despite all the digitalisation, museums remain analogue.

The museum as a place of experience may also remain a place of retreat from the digital world that is gradually overloading us – as a place of contemplation and recreation.

Sources:

Dilenschneider, Colleen: Musing On A Mobile App For Your Cultural Organization? Read This First (NEW DATA) [https://www.colleendilen.com/2019/05/01/musing-on-a-mobile-appl…; 11 August 2022]

EU Web Accessibility Directive [https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L2102&rid=1; 11 August 2022]

Haage, Anne: Digitale Barrierefreiheit. Grundlagen und Richtlinen. In: In: rheinform. Informationen für die rheinischen Museen 1/2022, ed. by Landschaftsverband Rheinland, pp 50 – 53

Heidsiek, Katie: Does it move you? Evaluating the impact of virtual reality on the visitor experience at the German Emigration Center. Bremerhaven 2019 [https://assets.dah-bremerhaven.de/assets/Deutsches-Auswandererhaus-museum4punkt0-VRStudie-COPYRIGHT-Deutsches-Auswandererhaus.pdf; 16 August 2022]

Loitsch, Claudia: Mit barrierefreien Multimedia-Guides mehr Besucher*innen erreichen. Ein Praxisbeispiel aus den Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden. In: rheinform. Informationen für die rheinischen Museen 1/2022, ed. by Landschaftsverband Rheinland, pp 44-49

Morrison, Debbie: Museum Apps: Why They’re Brutal and How to Fix Them [https://www.debbimorrison.net/museumsforreal; 11 August 2022]

WCAG 2.1 [https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/; 11 August 2022]

Discussion on Children’s Learning Effect by Digital Media during Museum Visiting: Based on an Empirical Survey of Museum Visitors

Wuyan Li, Postdoctoral Researcher, Shanghai Science and Technology Museum, Shanghai, China

Abstract

In recent years, the development environment of museums has changed in many ways. And children, as important visitors to many museums, are different from what they used to be. In this context, museums should seek to survive by strengthening their capacity to provide educational resources. The emerging digital technologies have opened up many new possibilities for museum education and has greatly enriched children’s learning experiences. However, the role of technology in the museum experience is ambivalent, with its effect being questioned or disputed, makes it important to examine the necessity and effect of its use on which this paper is focused. Through observations and interviews with 36 children and their companions in exhibitions of two museums in China, this study can preliminarily summarize the interactive learning behaviours, learning effect and influencing factors of children’s learning with digital exhibits during their visit. It turns out that interactive learning behaviour have three modes: children’s interaction with digital media exhibits, companions’ interaction with digital exhibits, and interaction between children and their companions. Most children with positive interactive behaviours through digital media cannot actually achieve the expected effect in all dimensions, and the relevant factors influencing effect can be categorised as physical, personal and social factors. On the basis of the findings, suggestions are made to optimise the design of digital media exhibits to improve children’s learning effect. In addition, significant and consistent differences in the learning behaviour and effect of digital media among children aged 3-6, 7-9 and 10-12 are also found.

Key Words Museum; Children; Digital Media; Learning Effect

Introduction

Museums today are in a new development environment full of opportunities and challenges (Loveland, M et al.2015). First, as non-profit, informal learning organisations, they faces fierce competition with other institutions, especially commercial ones, for the cultural capital of audiences, and the impact of the information explosion in this age makes people prefer to pursue short and fast information (which is the strength of for-profit organizations to produce), and museums are faced with the crisis that whether they can still attract visitors. Secondly, COVID-19 has profoundly changed the world, posing huge challenges to the on-site service of museums and increasing financial pressure(UNESCO 2021). Although more than half of museums in China are fully funded by the government, many of them still have been forced to get income through multiple channels and introduce market mechanisms to operate under financial pressure. At this time, attracting more visitors and providing a better museum experience has become an “inelastic demand”. Thirdly, the characteristics of visitors have changed dramatically, with people are in the “filter bubbles” result from algorithms(Eli Pariser 2011), leading to increasingly diverse needs and elusive visitors, and “reconceptualising the relationship between museums and visitors” has been considered to be one of the biggest challenges for contemporary museums. (Eilean Hooper-Greenhill 2000) In recent years, discussions in the museum world have been dominated by “new changes”, “new visions” and “new development”, and the definition of museums are changing drastically, indicating that museums, the institution that has been inherited for many years, urgently need to reform and meet the new needs of visitors in terms of learning and entertainment through new methods(Graham Black 2005).

Children are among the target visitors in many museums. Compared to adults, children have special characteristics in reading skills, cognitive abilities, life experiences and so on(David R.B et al. 2020)(Pagano, A., & Cerato, I. 2015), for example, they have a high degree of creativity and curiosity. There are many studies on children’s museum learning,and it is found that it presents different characteristics in learning behaviours, such as learning through touch, feeling, and imitation(Men, Y. et al. 2019). Since children’s visits are generally accompanied by adults, engaging children is an effective strategy to attract visitors of all ages(Zvyagintseva, L. 2018). Children are also different in new era. For example, the Z generation, who are digital natives, have many new needs. They are ‘immersed in technology'(Kraemer, H. 2018), and adept at using digital tools and have different learning styles, preferences and habits(Lessa, J. 2020). Therefore, under these backgrounds, museums should respond to the dramatic changes in the outside world and seek new survival through the reform of education supply.

Digital transformation is a highly valued solution put forward by global museum community. Ubiquitous digital media has completely revolutionised museum exhibitions, with a large number of museums have already commonly adopting digital media technologies such as digital projection, touchscreens, Augmented Reality(AR) and Virtual Reality(VR) as tools to interpretation, resulting in dramatic changes to exhibitions, exhibits and museum learning. Those promising technologies mentioned in 2010-2016 Horizon Report: Museum Education Edition published by the New Media Consortium NMC such as Mobiles, Location-Based Services, Gesture-Based Computing, Tablets, AR, VR, Smart Objects, Natural user interfaces, Games and Gamification, Networked Objects, are gradually shining into reality and play a part in museums, generating new devices, new models and new environments for communication(T. Smirnova, D. Vinck.2020) that not only contribute to improve the quality of content, enrich the perceptual experience of pleasure(Wang, Y., Yu, J. 2020)(Aimi F.H. et al. 2014), excitement and even deeper understanding, make children’s interaction with museums shift from looking to touching, engaging and even immersion, facilitate a lasting dialogue between visitors and exhibitions, and provide unprecedented opportunities for collaborative learning(Mohd N.S. et al. 2018;Zhang, Y. 2020; Aristova, U.V. et al. 2020), but change the learning paradigm(Papathanasiou-Zuhrt, D. et al. 2019). It also helps educators to better facilitate children’s meaning construction, bringing many benefits to them(Plowman, L., & Stephen, C. 2005; Loveland, M et al.2015). The use of technology has been so prevail that many museums even hold exhibitions full of digital media artworks, which ignite visits, and become internet sensations and museums reap the benefits of both social and economic success. All of this makes technology seem like a panacea for all problems.

Although technology offers great opportunities for museum displays, the practical effect has not yet been fully proven(Tay, J.L.MJ. 2021;Carrozzino, M., and M. Bergamasco. 2010; Candello, H. et al. 2020;Areti D. et al. 2019) and their negative effect cannot be ignored(Jessie Pallud 2017). The widespread use of digital media has raised concerns among educators and parents that it will be too entertaining and addictive(Cowan, K. 2019), or hinder the intake of knowledge(F. Braña Rey, D. Casado-Neira. 2014), discourage social interaction(Loveland, M et al.2015), and some conservative museums fear the virtual representations of objects will supersede the real objects for visitors(Stogner, M. B. 2009;Pop, Izabela Luiza and Borza, Anca. 2016;Roccetti, M., Marfia, G. & Bertuccioli, C. 2014), and some practitioners believe that as children in this age are growing up with technology, digital media will not be attractive enough(Linzer, D. 2013). In addition, the use of technology often means higher costs than many traditional exhibits, and those hardware invested in can quickly become out of date(Candello, H. et al. 2020). In many circumstances, museums’ strong desire to catch up with new technologies can easily lead to blindly using of digital media as a means to reshape exhibitions rather than a rational decision in order to improve real effect, so it is important to examine the necessity and effect of the use of digital media.

Methodology

Research Objective and Method

Qualitative research is applied to uncover children’s learning in museums through digital media. Existing studies rarely conduct systematic research on learning by digital media, and study focused on specifically on children. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following questions:

Q1: What types of digital media are used in museum learning?

Q2: What are the learning behaviours while children interacting with digital media in museums?

Q3: How effective is learning by digital media for children in museums?

Q4: What are the factors, which affect the digital media learning for children in museums?

Q5: How can digital media in museums be optimised to enhance children’s learning effect?

Data Collection and Analysis

This study uses qualitative emperical methods based on the research objectives, and the complexity of visitors and the difficulty of accessing children’s thoughts in particular. To prevent the researcher from intervening the natural learning condition of visitors, data were collected by using non-interventional observation of visitors and interviews after their interaction with digital media. Observation focuses on the behaviours, deductive effects and influencing factors of behaviour, and interviews focus on obtaining demographic data and self-reported effect of learning by digital media of visitors.

The empirical survey is conducted in the exhibitions of Shanghai Natural Museum and the Shanghai Astronomy Museum who have higher level exhibitions as well as more and newer digital media exhibits, can represent the current status of digital media applied in museums. 23 digital media exhibits of different types in the exhibitions were selected as observation points, coded S01-S23, and regard children those who interacted with the exhibits for more than one minute as effective interacting visitors, then observed children and their companions, and made detailed records of their behaviour and conversations during the interaction, such as visitors’ gestures, body movements and the duration of the interaction. When interaction ended, they were asked for consent and interviewed to examine the learning effect. As children are wary of strangers, some questions were asked by parents to help get answers. The survey was conducted in September-October 2021, 11:00-15:00 every time. Data of notes of 36 groups of visitors was collected, with 15 groups of children aged 3-6 years, 13 groups aged 7-9 years and 8 groups aged 10-12 years. Only 3 groups were repeated visitors, the others were all first-time visitors. The code of the observed child is followed by the a-d (for example, the 3rd visitor who interacted with S11 would be coded S11c).

The interview outline referred to the informal learning evaluation frameworks called General Learning Outcomes (GLOs) developed by the University of Leicester, and the Informal Science Education (ISE) framework developed by the National Science Foundation, which uses knowledge, attitude, skills, interest and inspiration as the dimensions to measure learning effect. The outline has three sections: basic information about the children, including demographic information such as gender, age, grade, and the relationship between the child and company; learning effect, including ease of use of the device, knowledge or skill learned, and whether enlightened, interest was enhanced, or attitude was changed; factors that influence learning.

Results

Classification of Digital Media in Museum Learning

Two museums have many digital media exhibits including those are usually used in museum field. To classify by function, there are three types:

Type I. Information integration. The exhibit integrates a large amount of relevant supplementary knowledge and other information into devices such as touch screens for interested visitors to search and browse.

Type II. Reality Alternative. By using audio, video and other digital media means, the exhibit makes up for the spatial or temporal absence of objects, scenes, phenomena and other real existence in museum field in the form of virtual demonstration/reappearance/real-virtual combination. They usually installed with other static exhibits (such as cultural relics, specimens) and physical scenes.

Type III. Gaming platform. The exhibit is only the carrier of the game, which is relatively independent from the exhibition. The content of the game is related to the exhibition, but can be interacted without other exhibits.

To classify by interaction, there are also three types:

Type a. Browse. No operation is required, and visitors only receive information such as text, video and other information by gaze.

Type b. Manipulate. Different contents in digital media are triggered by sounds, gestures or body movements. The responds are fixed, and the communication is still one-way.

Type c. Contribute. Different contents in digital media are triggered by sounds, gestures or body movements, but interaction can generate personalised results.

Among the digital media exhibits visitor interacting with in this study , 5 were Type I, 13 Type II, 6 Type III; 2 Type a, 20 Type b, 1 Type c; 5 Type Ib, 2 Type IIa, 9 Type IIb, 6 Type IIIb, and 1 Type IIIc 1. Except for 2 exhibits that require body movements to trigger, the rest are only to browse or operated by hand.

Learning Behaviours though digital media

Three types of visitors’ learning behaviours when interacting with digital media exhibits were observed, which are children’s interaction with digital media exhibits, children’s companions’ interaction with digital exhibits, and children’s interaction with companions.

Children’s interaction with digital exhibits are watching, listening, observing and operating the exhibits by sitting, standing or leaning on. Seven common gestures are used: drag/move, enlarge/shrink, rotate, tap, sweep, flick, and hold (Uta H., Sheelagh C. 2011). Body movements are standing, waving hands, griping and catching. Children’s learning behaviours are differ from different types of exhibits. Gestures used to interact with type I are relatively homogeneous, such as clicking and swiping on the screen, and keep watching; Behaviours visitor have when interacting with Type IIa depends on the size of the screen, visitors may walk when the screen is huge. Actions taken to interact with Type II and Type III depend on the shape of the device and interaction designed, which may require wearing devices. However, children’s behaviours are particularly different from adults, for they may not have the motivation of learning. Small children aged 3-6 have a large number of meaningless behaviours, such as touching, poking, and patting the touch screen, accounting for about 90% of their actions on average, and even repeatedly slapped defunct screens; the proportion of meaningful behaviours increased at the age of 7-9, and began to approach what adults act at the age of 10-12.

Children’s companions’ interaction with digital media exhibits depended on the identity of companions. If the child visits with peers, the behaviours will be same as the first type, and in the case of adults, there will be few meaningless interaction and most adults interact as designer’s intention, and thus be able to introduce to, instruct, guide, or discuss with children.

However, neither children nor adults are always able to accurately follow the pre-determined interaction. For example, S13a, an exhibit on turtle eggs hatching, indicates the days required for hatching by means of a circle progress bar, but some visitors assume the bar is to select and run their fingers over the circle, which didn’t trigger expected response.

Children’s interaction with companions include behaviours initiated by children and by companions. The former ones include introducing, demonstrating, rising questions and discussing, types of behaviours are differ with identity as well. There were no interaction with museum staff were observed, most children visited with parents, grandparents and peers. The latter ones include supporting, managing and intervening (Riedinger, K., Taylor, A. 2019). Some parents support learning by introducing, inducting and guiding; manage learning by pacifying and correcting, and sometimes have negative effect. Different parent-child relationship leads to different behaviours (Luo L., Kou X. 2020). Parents who ignore their children rarely interact with children or only react when children introduce or demonstrate; Parents prefer to instruct and control and have a great deal of managing and intervening behaviours; Parents collaborate and Negotiate with their children conduct more supportive behaviours. interaction between children and their peers are more likely to result in playing together or even have conflicts, generating meaningless interaction with digital exhibits, but many of them still build up relationship to explore together, and conduct supportive behaviours.

Learning effect though digital media

Comparing the judgments of learning effect by observing visitor behaviours with the self-reported effect reflected in the interviews, it can be found that the actual learning effect of children who conducted positive learning behaviours with digital exhibits and other people are generally not good enough in dimensions of knowledge, attitude, skills, interest and inspiration, especially in terms of knowledge dimension.

Among those digital media types, Type I is the least effective for small children across all dimensions of learning, with meaningless behaviours decreasing with age increasing. Literacy skill is a major threshold, and illiterate children will lose interest even when parents explain the content to them. Among Type II exhibits, Type IIa is a one-way communication that seems to fall into the mould of didactic education in perspective of constructivism(George E. Hein. 1998), and it can’t be denied that just gazing is not so easy to transmit knowledge, but it can generally provoke intuitive feeling and have more visually stimulating, especially for small children, and more likely to arouse interest than static objects. Type IIb have effect of all dimensions when the content is accurately understood, but a major challenge with the virtual-real exhibits is children’s misunderstanding of the physical object showed on the screen. For example, although S17a interacts with the meteorite on the touch screen through AR, he didn’t know the meteorite on the screen is exactly the object behind the screen. The learning effect of Types IIa and IIb are both increased in with parents’ explanation, with potential effects on knowledge, attitudes, interest and inspiration; Type III was most likely to stimulate interest and lead to immersion, results in the poor effect of knowledge, but skill dimension may be improved, like s18b’s father stating “he didn’t know how to play this game on the screen at first, but slowly figured it out “. Types IIIb and IIIc were easy to stimulate children’s interest, but the effect was poorer in all other dimensions.

In addition to individual learning effect, some exhibits can enhance learning effect by facilitating social interaction. When the exhibitions are crowded, some digital exhibit occupied could also have similar effect for other visitors those who were waiting and gazing beside, while some are strong experiential exhibits ones which will have poor learning effect. Different companions also lead to different learning effect, for example some children show the potential for peer learning by increased interest and engagement in exhibits with complementary knowledge, cognitive ability and skills(Liu X.L. 2015).

It’s also observed that the advantages of digital media are not absolute. Traditional mechanical means such as physical buttons which are regarded as technology belonged to the last generation, are still popular.

Relevant factors affecting the learning effect of digital media

The survey reveals that there are many factors that influence learning effect. Taking Falk’s museum learning context model as an analytical framework, those factors can be generalized as three aspects: personal context, social context and physical context.

Physical factors. The design and operational condition of the digital media exhibits themselves have the greatest impact. Damaged or out-of-service equipment was the most frequently mentioned problem. And if the content is too difficult or too complex to understand, children will also feel confused; Inappropriate design, including the problems that interactive instructions are not obvious enough, results in visitors’ wrong way to interact; and dismatching design to content, will easily cause misunderstood. Technology still can not achieve some envisaged learning effect. For example, although the natural user interface is typically effective, it is still difficult for the actually adopted technologies such as Kinect to sense motions in a truly “natural” manner, which in many cases frustrates visitors. The museum environment can also affect children’s learning, for example, due to visitors are so crowded and interactive exhibits are relative attractive to children (especially games), often resulting in many children have to wait in queues become irritable.

Personal factors. Some children’s common characteristics affect digital media learning, on the one hand, physical characteristics such as height, physique and cognitive level that differ from those of adults, such as digital exhibits that are too tall and parents have to lift children up in order to interact. On the other hand, there are psychological characteristics, such as the children’s preference for dynamic devices, “I like things that will move and can be manipulated (S12a)”; the touch and play instincts, and the tendency to persue the completion of interaction rather than learning in the process with impatience. Such as S20, although he interacted alone for 15 minutes and excitedly showed the exhibits to his father, he did not actually read the instructions. His father then pacified and guided him:”This is science, it’s not a game you know…This is not a riddle, you can’t just see one thing and make decision immediately…” which calmed the boy down and made him begin to seriously read the content.

Individual differences in knowledge structures, interests and relevant experience among children also affect learning. Interactive digital media such as touchscreens require texts to introduce knowledge or instruct how to operate, so literacy levels largely determine whether visitors can interact correctly. If children have learnt related knowledge, it will promote understanding. Among those children with good learning effect, most of them know some knowledge about the exhibit told by kindergarten teachers (S19a), books (S13b), documentaries (S11a); Interest is a fundamental motivation for children to learn. S05a was not interested in natural history, so he have completely meaningless interaction with digital exhibits for long periods of time while his father loves natural history museums so much that he would like to foster S05a’s interest by taking him here.

Social factors. It is mainly reflected in the influence of different companions. For example, in the parent-child families surveyed, families that adopt positive guidance and other support or management behaviours, children’s learning effect is generally better than that of other families. The lack of guidance will have a negative impact on children’s learning. For example, S21a interacted with the game which is too difficult to get a high score, her parents blamed her for not being accurate enough, which deviated from the original intention of the game. Parents’ motivations also had impact, with most parents believing that gaining knowledge and experience was the main motivation for visiting, and therefore encouraging children to explore, even if they did not understand the meaning, they would still actively guide them, S03a’s mother believed that “children will absorb what they are interested in …… and form the concept” and S20a’s mother said that “bringing her to visit is not to gain knowledge directly but learn something gradually through exploration. Now it may be just a fresh thing for her, and by one day, she may suddenly understand.”

Discussion

All types of digital media used in museum exhibits have actual or potential effect to enhance museum learning, but neither can fully achieve all dimensions of learning effect, and most problems exist because the characteristics and potential of the digital media type do not fit with actual conditions. Most Type I exhibits are designed for adults, but children are usually attracted by touch screens. So when designing exhibits by using Type I, possibilities of interaction from small children should be considered. Attempts can be made to cater for both children and their companions in the interface, such as having a visual video and simple texts at the same page on the screen, with the texts are written for adults in many pages and when pages are turned, the video continues to play in order to engage children and reduce their impulse to make meaningless interaction.The learning effect of Type II for children relies on how deeply they understand the knowledge delivered by the exhibit, and the increase in the knowledge dimension leads to increase in the other dimensions, so improvements need to be made primarily through displaying knowledge more concise to enhance children’s understanding when they learn on their own, and to help their companions to build scaffolding for them. Virtual demonstrations and virtual reality exhibits should be made more intuitive so that children can relate the graphics to real objects, real images should be supplemented with audio narration to bridge the gap between illiterate children and knowledge. Natural user interface should be used only when it can be truly “natural”.Although Type III reduces the cognitive load children will have when trying to figure out how to interact and has a very rapid and huge appeal to children, it tends to make children too obsessed with digital media and occupied the time which should be spend enjoying other objects and scenes, and the significance of onsite museum learning is somewhat lost.On the one hand, the design of the Type IIIb game should avoid complex rules and excessive difficulty, and make visitors use digital media devices more accurate by methods such as integrating knowledge of objects and others with intuitive elements (such as simple icons), making more direct connections between icons and the game rules, designing gestures and flows in the same way as those commonly used in tablets used in daily life, using easy-to-understand texts to help children just able to read and helping parents quickly understand the rules. In a limited space, installed more than one devices for the same game rather than for some different games in order to avoid children spending too much time waiting in queues as well as the negative effect of children’s being addicted to the game. In addition, as Type IIIc exhibits do not need to follow rules set before interaction and have the potential to spark children’s creativity and promote social interaction with companions, the number of this type of digital media should be increased, not only to promote parent-child family and peer learning, but also to develop staff involvement in children’s interaction. For Type b and Type c, digital media devices of different heights can also be set up for the same content to facilitate the interaction of visitors of different ages, while making content shown more dynamic and vivid, as well as increasing physical participation and making the exhibits more body-cognitive. The use of new technical means to achieve personalised recommendations can also be explored. Except for the individual exhibit design, it can be considered from the whole exhibition. In order to fully enhance the various dimensions of the learning effect during the visit, different types of digital media can be interspersed throughout the exhibition so that the pace of visiting can be controlled as well. Also take character of different types into account when thinking of recommend path for children.

Additionally, after a preliminary analysis of literature and survey results, it is found that not only children have different characteristics from adults, but there are also some significant differences in children’s learning behaviours and effects of different age groups, which are consistent with some theories and viewpoints in psychology and pedagogy. It has not been covered in past research. The exploration of children’s segmentation will be more conducive to the improvement of learning effect. This paper attempts to summarize some characteristics, which may provide a reference for the digital media design in future museums.

Children aged 3-6 years are mostly unable to receive the knowledge conveyed by digital media exhibits, but are very active and engaged in interest dimension. Meaningless interactive actions such as tapping and poking at screens are instinctive and driven by Interest-Curiosity, and they are strongly fond of interacting with all types of digital media exhibits, but exhibits that communicate information in one-way, such as videos, are difficult to attract prolonged attention if the content is not visually vivid, whereas exhibits that provide real-time feedback through touch and other interaction are capable of sustained interaction. However, this engagement is not based on the interest in the content, but rather on a great curiosity about the digital incentive and a strong expectation of a ‘treat’ from feedback after the interaction, combined with a lack of literacy and basic knowledge that leads to a failure to understand the content. The effect of companions’ guidance is very limited. The research of cognitive science suggests that stimulating perceptual curiosity activates the hippocampus and is beneficial for enhancing learning effect. Parents of preschoolers do not take their children to museum with the motivation of making their children get knowledge immediately, but rather to activate their memories when they are reintroduced to the same knowledge in the future, as a seed for future learning.

Children aged 7-9 years are able to recognise texts on digital media exhibits and therefore interact with them in a more logical way than preschoolers, learning effect in dimensions of knowledge, interest and attitude are enhanced, and the positive effects of parental guidance begin to emerge. They begin to develop an intellectual curiosity due to the deprivation of access to specific information, which stimulates the urge to explore and generate effective learning. But at this age, the influence of personal and social contexts on physical contexts begin to emerge since most children in this age group have not learnt content presented in the digital media exhibits in formal education and lack a certain understanding of what the exhibits are intended to convey, but those who have been taught by teachers or parents have much better effect.

While the interest-curiosity to interact with digital media exhibits is still present in children aged 10-12, as their cognitive level and knowledge grows, the effect in the knowledge dimension lifts significantly, a strong intellectual curiosity is formed, the ability to self-learn is present and the pattern of parent-child interaction changes significantly. The difficulty of drawing children’s attention for long periods of time increases, and some children may even be reluctant to interact with digital media exhibits that stimulate interest-curiosity, the effect of parental guidance drops again.

The design of digital media exhibits should take these three main children groups into account. The third group is already closer to adults and need mainly add interest and the respect of independent learning and exploration, the first group in particular needs to avoid using texts and add audio, and the second group can be helped by providing a manual of basic knowledge and other guides.

Conclusion

This study uses observation and interview methods to investigate the children’s learning through digital media in Shanghai Natural History Museum and Shanghai astronomy museum, trying to summarize interactive learning behaviours, measure learning effects, and explore the factors that may influence learning. The results show that in the process of children’s interactive learning through digital media in museum, diversified interactive behaviours are conducted, including children interacting with digital media, their companions with digital media, and with their companions, but the actual learning effect is not as good as it seems to have. No matter which type of digital media, they cannot achieve learning effects in all dimensions which may be influenced by physical factors such as digital media exhibits themself, personal factors such as children’s common characteristics and individual differences, and social factors such as the characteristics of companions. Inspired by this, the design of digital media exhibits should be based on the characteristics and potential of different digital media types, fully take children’s special needs into account, and refine various relevant influencing factors, so that the advantages of digital media can be brought into fully play.

The limitation of this survey was that it carried out in areas with a high degree of economic development. Because of the pandemic, most visitors observed and interviewed were locals with relatively good digital literacy. In the future, the survey can be extended to children in less developed areas to examine the impact of the “digital divide” on learning through digital media in museums.

Reference:

- Aimi F.H., Mohd Z.M.T., Aida A. 2014. ‘The Integration of Interactive Display Method and Heritage Exhibition at Museum’. Social and Behavioural Sciences, Vol.153, No.16. pp. 308-316.

- Areti D.,Ian R.,Eva H. 2019.’ The MUSETECH model: A comprehensive evaluation framework for museum technology’. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage. 12, No.1, pp.1-22.

- Aristova, U.V., Rolich, A.Y., Staruseva-Persheeva, A.D., Rolich, A.O. 2020. ‘Digital Museum Transformation: From a Collection of Exhibits to a Gamut of Emotions’. In: Alexandrov, D.A., Boukhanovsky, A.V., Chugunov, A.V., Kabanov, Y., Koltsova, O., Musabirov, I. (eds) Digital Transformation and Global Society. DTGS 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, Vol.1242. Cham: Springer, pp419-435.

- Candello, H., Barth, F., Carvalho, E., Cotia, R.A.G. 2020. ‘Understanding How Visitors Interact with Voice-Based Conversational Systems’. In: Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E. (eds) Design, User Experience, and Usability. Design for Contemporary Interactive Environments. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 12201. Cham: Springer, pp.40-55.

- Carrozzino, M., and M. Bergamasco. 2010. ‘Beyond virtual museums: Experiencing immersive virtual reality in real museums’. Journal of Cultural Heritage, Vol.11, No.4. pp. 452-458.

- Cowan, K. 2019. ‘Digital Meaning Making: Reggio Emilia-Inspired Practice in Swedish Preschools’. Media Education Research Journal, Vol.8,No.2.pp.11–29.

- David R.B.,Jeffrey K.S.2020.’Inside the Digital Learning Laboratory:New Directions in Museum Education’. Curator: The Museum Journal, Vol.63,No.3. pp. 371-386.

- Eli Pariser.2011.The Filter Bubble:What the Internet Is Hiding from You.Penguin Press.

- Eilean Hooper-Greenhill. 2000. The Rebirth of the Museum. Museums and the interpretation of visual culture. London: Routledge, pp.151-162.

- Braña Rey, D. Casado-Neira. 2014. ‘Musem’s Visitors and ICT: Analysis on Sociolcultural Variables and Level of Digital Alphabetisation of Visitors’. INTED2014 Proceedings 8th International Technology, Education and Development Conference. pp. 3640-3646.

- George E. Hein. 1998. Learning in the Museum. Routledge,OX. p25.

- Graham Black.2005.The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jessie Pallud. 2017. ‘Impact of interactive technologies on stimulating learning experiences in a museum’. Information & Management, Vol.54, No.4. pp. 465-478.

- Kraemer, H. 2018. ‘“Media Are, First of All, for Fun”: The Future of Media Determines the Future of Museums’. In: Bast, G., Carayannis, E., Campbell, D. (eds). The Future of Museums. Arts, Research, Innovation and Society. Cham: Springer, pp. 81-100.

- Lessa, J. 2020. ‘Water Museums and Digital Media: Two Case Studies on Digital Media in Water Museums’. In: Rebelo, F., Soares, M. (eds) Advances in Ergonomics in Design. AHFE 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Vol 955. Cham: Springer, pp.349-358.

- Linzer, D. 2013. ‘Learning by doing: Experiments in accessible technology at the Whitney Museum of American Art’. Curator: The Museum Journal, Vol.56, No.3. pp. 363-367.

- Liu X.L. 2 ‘A study on the relationship between the level of learning motivation, peer interaction and academic performance of primary school students’. Shanghai Research on Education, No.4. pp. 32-35.

- Loveland, M., Buckley, B., Quellmalz, E. 2015. ‘Using Technology to Deepen and Extend Visitors’ interaction with Dioramas’. In: Tunnicliffe, S., Scheersoi, A. (eds) Natural History Dioramas. Dordrecht: Springer, pp.87-104.

- Luo L., Kou X. 2020. ‘Observational Research on Parent-Child Interaction Behaviours in Museum and Promotional Strategies: Taking Shanghai Science and Technology Museum as an Example’. Studies on Science Popularization, Vol.5, No.68. pp. 89-96+111.

- Men, Y., Chen, R., Higgett, N., Hu, X. 2019.’ A Study to Improve Education through Gamification Multimedia in Museum’. HFE 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing,vol 795.pp. 294-304.

- Mohd N.S., N.F., Ghazali, M. 2018.’ A Systematic Review on Digital Technology for Enhancing User Experience in Museums’. In: Abdullah, N., Wan Adnan, W., Foth, M. (eds) User Science and Engineering. i-USEr 2018. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 886. Singapore:Springer, pp. 35-46.

- Pagano, A., & Cerato, I. 2015. ‘Evaluation of the educational potentials – interactive technologies applied to Cultural Heritage’. 2015 Digital Heritage, 2, 329-332.

- Papathanasiou-Zuhrt, D., Thomaidis, N., Di Russo, A., Vasile, V. 2019. ‘Multi-sensory Experiences at Heritage Places: SCRIPTORAMA, the Black Sea Open Street Museum’. In: Vasile, V. (eds) Caring and Sharing: The Cultural Heritage Environment as an Agent for Change. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Cham: Springer, pp.11-49.

- Plowman, L., & Stephen, C. 2005. ’Children, play, and computers in pre-school education’. British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol.36, No.2, pp 145-157.

- Pop, Izabela Luiza and Borza, Anca. 2016. ‘Technological innovations in museums as a source of competitive advantage’. Proceeding of the 2nd International Scientific Conference SAMRO 2016 , Vol. 1. pp. 398-405.

- Riedinger, K., Taylor, A. 2019. ‘Leveraging Parent Chaperones to Support Youths’ Learning During an Out-of-School Field Trip to a Marine Science Field Station;. In: Fauville, G., Payne, D., Marrero, M., Lantz-Andersson, A., Crouch, F. (eds) Exemplary Practices in Marine Science Education. Cham: Springer. Pp. 59-80.

- Roccetti, M., Marfia, G. & Bertuccioli, C. 2014. ‘Day and night at the museum: intangible computer interfaces for public exhibitions’. Multimed Tools Appllication,69. pp. 1131-1157

- Stogner, M. B. 2009. ‘The media-enhanced museum experience: Debating the use of media technology in cultural exhibitions’. Curator: The Museum Journal, Vol.52, No.40. pp. 385-397.

- Tay, J.L.MJ. 2021. ’Digital Technologies and Children: Does more Digital Interactivity Make for Better Learning?’. In: Holloway, D., Willson, M., Murcia, K., Archer, C., Stocco, F. (eds) Young Children’s Rights in a Digital World. Children’s Well-Being: Indicators and Research, Vol.23. Cham: Springer. pp. 161-175.

- Smirnova, D. Vinck. 2020. ‘The Social and Sociotechnical interaction of Visitors at a Digital Museum Exhibition:The Montreux Digital Heritage Lab’. Environnement numérique et musées.Vol.15, No.1. pp. 43-66.

- 2021. [Online].’Museums around the world in the face of COVID-19, 2021’. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000376729_eng[Accessed 10 August 2022].

- Uta H., Sheelagh C. 2011. ‘Gestures in The Wild:Studying Multi-Touch Gesture Sequences on Interactive Tabletop exhibits’. Proceedings of the International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. pp. 3023-3032.

- Wang, Y., Yu, J. 2020. ‘Media Convergence in Information Transmission in Museum Space’. In: Di Bucchianico, G. (eds) Advances in Design for Inclusion. AHFE 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing.954. Cham: Springer, pp.310-316.

- Zhang, Y. 2020. ‘Research on Design of Children’s Experiential Space in Museum Based on Interaction Concept: Take Perth, Australia as an Example’. In: Ahram, T., Falcão, C. (eds) Advances in Usability, User Experience, Wearable and Assistive Technology. AHFE 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Vol 1217. Cham: Springer, pp. 61-66.

- Zvyagintseva, L. 2018. ‘It is Our Flagship: Surveying the Landscape of Digital Interactive Displays in Learning Environments’. Information Technology and Libraries. Vol. 37, No.2.pp. 50-77.

The impact of lockdown on public engagement and involvement in small and peripheral museums: the case study of Swapmuseum digital strategy

Carola Gatto, Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Salento, Italy

Elisa Monsellato, Swapmuseum

Abstract

Swapmuseum is a project of cultural participation, based on mutual exchange between teenagers, between 16 and 29 years old, called “swappers”, small museums and companies. The project aims to involve an under-served target group in museums, that of teenagers, in order to carry out non-specialised voluntary activities, agreed upon with the scientific direction of the museum. The exchange process is as follows: museums identify activities suitable for their own context, such as communication activities (contests, blogging, social), promotion (creation of memory archives, organisation of visits and events for teenagers); fruition (emotional audio guides, sensory paths, simplified captions, maps, treasure hunts). The young volunteers can choose the activities according to their aptitudes, in exchange for benefits commensurate with the number of hours spent, ranging from a series of discounts granted by affiliated shops, to the possibility of using cultural services, to the recognition of training credits.

The project was launched in 2016 with funding under the “Con Il sud che partecipa” call for proposals by Fondazione con il Sud, and has been refinanced several times by various public and private bodies to date. Geographically, the project is located in the Apulia region (Italy), and has intervened precisely in the consolidation of the museum network, acting in particular on small and peripheral museums.

Due to the lockdown caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, all project partner museums were forced to close. Therefore, Swapmuseum invested in the creation of digital content using different online tools to reach and engage the target group. The project turned into a transmedia experience during the lockdown, thanks to the integration of innovative digital tools and proven engagement strategies. Digital has thus become a tool to increase active participation, as it contributes to the expansion of the museum world through user-generated content, triggering processes of enjoyment and emotional involvement. Storytelling takes on the connotations of a transmedia narrative, becoming a collective narrative.

This paper analyses the data and outputs of the project before and after the lockdown, investigating the ongoing transformation in terms of engagement and effectiveness of the methodology.

Introduction

Swapmuseum is a cultural participation project that has been active since 2016 in Apulia, a region in southern Italy, based on mutual exchange among young people, between the ages of 16 and 29, called “swappers,” small museums and companies.

Because of the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic, all of the project’s partner museums suffered a forced closure. Therefore, Swapmuseum invested in digital content creation, using various online tools to reach and engage its target audience. This paper analyzes the transformation of the audience engagement and development process, in terms of the effectiveness of the strategy and tools, implemented by the team precisely in reaction to the forced and prolonged closure of the museums. In fact, during the pandemic we were faced with two orders of problems:

- On one side, teenagers were increasingly isolated with a consequent impact on their mental health.

- On the other side, museums were forced to close, and they had to manage an increasing marginality and loss of all the work done until then.

We decided to turn these problems into opportunities by rethinking the strategy and choosing to move online the whole steps of Swap’s activities, thanks to the collaboration of museums staff.